One of the reasons the long US short RoW trade has dominated is, many DM countries have the trade on, either implicitly or explicitly, or both! Going forward, the question is, is the virus enough of a force to change these dynamics. I think it is, but it will take time. The French+German proposal today could be the start of that change.

Sections:

- How did we get here. Globalization ended in 2011 and no one adjusted. Export based policy and high savings rates reinforced each other even as globalization forces weakened starting in 2011. The dollar was both rewarded as the place that could accommodate this excess savings but also reinforced the dynamic by inflicting pain on export based economies.

- Too many savers post GFC. Everyone wanted to save, governments pulled back, households were in balance sheet recession (Koo) and corporates had very few attractive investment options. If everyone is saving, someone must be dissaving in a big way. The US did and was rewarded for it. We are operating in a world where there is a massive excess of capital vs. productive places to put it. Which is why valuations on high quality assets able to absorb this savings is so high.

- This dynamic neutered monetary policy. Via slower global growth and an immense demand for safe assets, the neutral level of interest was crushed. In that world, monetary policy is not really easing but just keeping pace. If policy can't get inside r*, its adjusting, not easing.

How did we get here

Going back pre 2008. China wanted to be the world's manufacturer but it didn't want to take the exchange rate adjustment that came with it. And if China didn't want to accept a higher exchange rate, the countries that were selling to them, surplus Asia and Europe, weren't going to be keen to have one either. So there is a gap between purchasing power and money coming, that imbalance is worked out via higher savings rate and a continued rise in the current account balance.

So as trade grows, and countries fight against exchange rate adjustments, rising incomes don't get spent because they are effectively constrained by an artificially weak exchange rate. The world then had a choice, rebalance surpluses into buying more US goods via a fair exchange rate regime or just send into the US via demand for financial assets. They chose the latter.

This is one of the reasons the status quo has persisted. US manufacturing never got a chance because it's constrained via a strong FX and it is why there was never a meaningful pickup in consumption as a percentage of growth in the surplus world. Relative exchange rate regimes reinforced this dynamic of, surplus world doesn't spend and the US doesn't save.

The negative dollar spillover

The dollar problem from this became more obvious as Chinese demand began to structurally fall as the credit impulse weakened. Much of the global economy had a fairly simple model, export to china and recycle surplus' into USD. Exchange rates stay tame and the money is better in USTs/US IG/ Tech sector etc. than anywhere else.

However, the financial side of the economy began to inflict pain on the real side. Money comes into the US, the dollar goes up, and that slows global trade. But it also set up a more troublesome effective doom loop. The dollar would rise, inflict pain on global trade, and then rise even more because the US is a relatively closed economy and less exposed to global trade. And what has been the only way out of this doom loop as post GFC global trade has been relatively weak, Chinese credit expansions.

It is not a coincidence that the only time we have seen real sustained USD weakness since the GFC is post China stimulus episodes (arrows meant to mark three most significant Chinese credit expansions).

Globalization died in 2011, no one adjusted

One of my favorite charts is from Hyun Song Shin at the BIS, ratio of world goods exports to world GDP. It shows a pretty remarkable fact, globalization was dying before Brexit, the Trump election and the trade war.

Despite this post crisis shift, growth composition for many advanced economies has been incredibly sticky with exports still making up over 30% of GDP in much of Asia and Europe.

These two charts are structurally disinflationary. World GDP has changed, but advanced country growth composition has not. And the problem is, from a policy perspective, the response has been to chase after lost external demand instead of reforms that rebalance the composition of domestic growth more towards consumption.

If we look at European policy making from post Euro crisis on, that is basically what happened. External demand started falling, and the reaction was, we'll try adjusting the currency to rebalance. This is how Europe got to negative interest rates while running primary surpluses. The reaction was to chase demand that wasn't coming back instead of investing domestically. That is basically what nirp is, another way of weakening the currency at the expense of domestic demand (local credit channel). Nirp ends up being a sort of tradeoff between the external and domestic sectors of the economy. The world doubled down on trying to save imported demand instead of figuring out how to grow internally.

Massive savings rates, a policy failure

As the world economy was doubling down on an economic model that was clearly structurally broken, savings rates continue to move higher as investment doesn't seem that compelling in weak NGDP world. The world economy shifted and Asia+Europe didn't get the message, so the imbalance between savings and investment grows even wider. And to add onto this, governments were running fiscal surpluses....

So what do we have now. A balance sheet recession with both the private and public sector trying to save. So savings rates in places like East Asia hit 40% of regional GDP. The gov't wants to run a primary surplus, households and business are either repairing balance sheets or are not seeing attractive investment options because NGDP is low. So where does all this money go..... Financial markets have to absorb it. One problem is, the amount of savings in Asia and Europe was far bigger than the size of their domestic asset markets.

While governments weren't spending, monetary policy was doing QE, removing the few government bonds from the market. And, on average, Asia + Europe lifer insurer assets are over 12x the size of their respective domestic IG bond markets according to the IMF's October 2019 GFSR. So there is no risk free assets and not nearly enough investment grade bonds. So where does the money go if there's no place for it at home, to whomever who can absorb it, which has always been the US.

As Bernanke said in 2007, you want to explain Greenspans "conundrum" here it is. The world saves and funnels it into the US. Term premia never had a chance......

The Japan example

Sections:

- How did we get here. Globalization ended in 2011 and no one adjusted. Export based policy and high savings rates reinforced each other even as globalization forces weakened starting in 2011. The dollar was both rewarded as the place that could accommodate this excess savings but also reinforced the dynamic by inflicting pain on export based economies.

- Too many savers post GFC. Everyone wanted to save, governments pulled back, households were in balance sheet recession (Koo) and corporates had very few attractive investment options. If everyone is saving, someone must be dissaving in a big way. The US did and was rewarded for it. We are operating in a world where there is a massive excess of capital vs. productive places to put it. Which is why valuations on high quality assets able to absorb this savings is so high.

- This dynamic neutered monetary policy. Via slower global growth and an immense demand for safe assets, the neutral level of interest was crushed. In that world, monetary policy is not really easing but just keeping pace. If policy can't get inside r*, its adjusting, not easing.

How did we get here

Going back pre 2008. China wanted to be the world's manufacturer but it didn't want to take the exchange rate adjustment that came with it. And if China didn't want to accept a higher exchange rate, the countries that were selling to them, surplus Asia and Europe, weren't going to be keen to have one either. So there is a gap between purchasing power and money coming, that imbalance is worked out via higher savings rate and a continued rise in the current account balance.

So as trade grows, and countries fight against exchange rate adjustments, rising incomes don't get spent because they are effectively constrained by an artificially weak exchange rate. The world then had a choice, rebalance surpluses into buying more US goods via a fair exchange rate regime or just send into the US via demand for financial assets. They chose the latter.

This is one of the reasons the status quo has persisted. US manufacturing never got a chance because it's constrained via a strong FX and it is why there was never a meaningful pickup in consumption as a percentage of growth in the surplus world. Relative exchange rate regimes reinforced this dynamic of, surplus world doesn't spend and the US doesn't save.

The negative dollar spillover

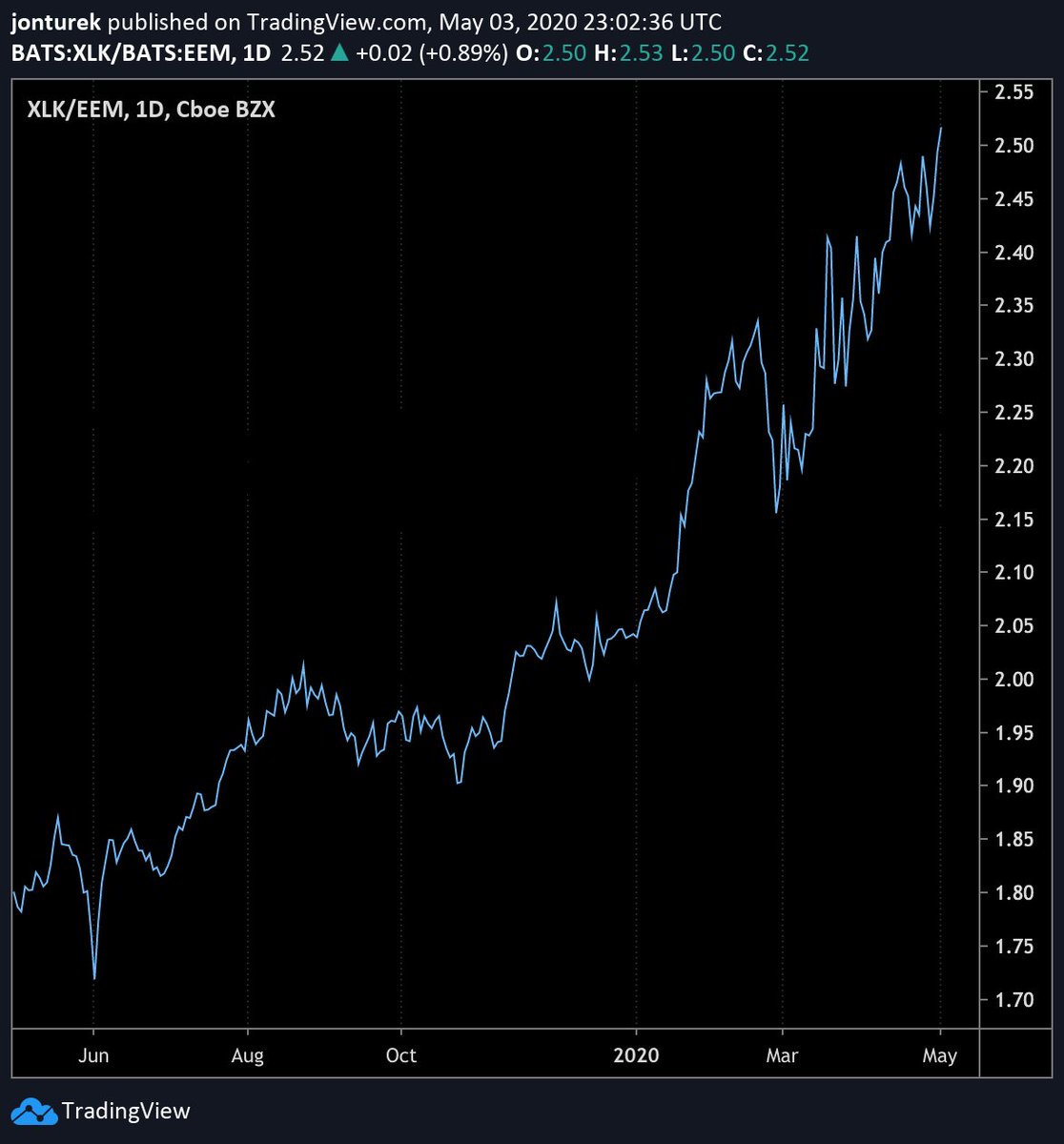

The dollar problem from this became more obvious as Chinese demand began to structurally fall as the credit impulse weakened. Much of the global economy had a fairly simple model, export to china and recycle surplus' into USD. Exchange rates stay tame and the money is better in USTs/US IG/ Tech sector etc. than anywhere else.

However, the financial side of the economy began to inflict pain on the real side. Money comes into the US, the dollar goes up, and that slows global trade. But it also set up a more troublesome effective doom loop. The dollar would rise, inflict pain on global trade, and then rise even more because the US is a relatively closed economy and less exposed to global trade. And what has been the only way out of this doom loop as post GFC global trade has been relatively weak, Chinese credit expansions.

It is not a coincidence that the only time we have seen real sustained USD weakness since the GFC is post China stimulus episodes (arrows meant to mark three most significant Chinese credit expansions).

Globalization died in 2011, no one adjusted

One of my favorite charts is from Hyun Song Shin at the BIS, ratio of world goods exports to world GDP. It shows a pretty remarkable fact, globalization was dying before Brexit, the Trump election and the trade war.

Despite this post crisis shift, growth composition for many advanced economies has been incredibly sticky with exports still making up over 30% of GDP in much of Asia and Europe.

These two charts are structurally disinflationary. World GDP has changed, but advanced country growth composition has not. And the problem is, from a policy perspective, the response has been to chase after lost external demand instead of reforms that rebalance the composition of domestic growth more towards consumption.

If we look at European policy making from post Euro crisis on, that is basically what happened. External demand started falling, and the reaction was, we'll try adjusting the currency to rebalance. This is how Europe got to negative interest rates while running primary surpluses. The reaction was to chase demand that wasn't coming back instead of investing domestically. That is basically what nirp is, another way of weakening the currency at the expense of domestic demand (local credit channel). Nirp ends up being a sort of tradeoff between the external and domestic sectors of the economy. The world doubled down on trying to save imported demand instead of figuring out how to grow internally.

Massive savings rates, a policy failure

As the world economy was doubling down on an economic model that was clearly structurally broken, savings rates continue to move higher as investment doesn't seem that compelling in weak NGDP world. The world economy shifted and Asia+Europe didn't get the message, so the imbalance between savings and investment grows even wider. And to add onto this, governments were running fiscal surpluses....

So what do we have now. A balance sheet recession with both the private and public sector trying to save. So savings rates in places like East Asia hit 40% of regional GDP. The gov't wants to run a primary surplus, households and business are either repairing balance sheets or are not seeing attractive investment options because NGDP is low. So where does all this money go..... Financial markets have to absorb it. One problem is, the amount of savings in Asia and Europe was far bigger than the size of their domestic asset markets.

While governments weren't spending, monetary policy was doing QE, removing the few government bonds from the market. And, on average, Asia + Europe lifer insurer assets are over 12x the size of their respective domestic IG bond markets according to the IMF's October 2019 GFSR. So there is no risk free assets and not nearly enough investment grade bonds. So where does the money go if there's no place for it at home, to whomever who can absorb it, which has always been the US.

As Bernanke said in 2007, you want to explain Greenspans "conundrum" here it is. The world saves and funnels it into the US. Term premia never had a chance......

The Japan example

The Japanese financial economy was given a tricky hand. The BoJ owns over 50% of the JGB market. And other than a post Abenomics three arrow blip, bank lending never really went anywhere. So we had this immense transfer of JGB holdings from financial sector to the BoJ. Combine the financial world with massive non bank sector (Lifers etc.) and you get a +3 trillion dollar positive NIIP position. Japanese demand for foreign assets grows every year and it is perfectly logical. Lifer assets are almost 25x the size of their domestic IG bond market and the BoJ owns half the JGBs, what else was there to do.

Another example of this, but with very different characteristics has been Taiwan (5th biggest NIIP in the world). In Taiwan, life insurance asset are over 150% GDP. Creating this imbalance has been a central bank that has repressed the exchange rate to defend the tradeable goods sector and now almost more importantly the non bank financial sector which has built up a very large implicit and explicit FX position. These three Asian economies are sending over 1.4 trillion USD into US credit markets.

The savings glut killed monetary policy

This global savings imbalance has created a big problem for monetary policy.

1) It is a position that is effectively short NGDP. If both private and public sector has a savings impulse, both growth and inflation fall. As the world is highly integrated, those conditions are exported. If r* is falling in Asia and Europe, it will be falling in the US as well.

2) So there are two ways excess savings relate to the neutral level of interest. First, it leads to lower growth as money cannot find productive places to invest or spend. Second, a key part of the calculation for the r* is a the demand for safe assets. So growth is slow and savings leads to a heightened demand for safe assets, interest rates around the world fall.

3) This has contributed to a smaller monetary policy impetus. One, it has driven policy rates around the world to the lower bound. But two, it has never really given policy a chance. We know that rate of accommodation (excluding LSAPs/forward guidance) of monetary policy is the stance of policy relative to the neutral level of interest, which of course is unknowable in real time. However, if global savings via slower global growth and an immense demand for safe assets is crushing the neutral level of interest, then monetary policy is not really easing but just keeping pace. If policy can't get inside r*, it's not really easing, it's adjusting. Said another way, savings have forced CBs to cut in order to not be tightening.

r* has become more and more a global phenomena. Data is from Jorda and Taylor, "Riders on a Storm" paper from last years Jackson Hole.

EM has had an uneven relationship with this savings backdrop

The spillover of this global savings backdrop and DM central banks at the lower bound is, the carry trade. In EM, the carry trade was executed in two stages. First, EM's issued in FX denom (Eichengreen original sin), that didn't work. The way EMs fixed this is by issuing a lot more in local currency and given how low DM yields are, INDOgbs or SAGBs, became very attractive. The problem now is original sin redux (Carstens&Shin). It is difficult for these markets to handle this sort of inflow and countries like South Africa, Indonesia, Mexico, end up with around 40% of the local government bonds in the hands of non resident portfolio flows.

So while yes, it is an advantage that low DM rates have forced capital into parts of the world that need it to further their development, it has come at the cost of volatility. These swings in capital flows since the GFC have become the new normal. EM has way bigger issues than capital flows, but these massive oscillations may have ended up doing more harm than good. This is of course nothing new for EM but this backdrop has helped foster a new vulnerability.

Overall: These all seem to be separate macroeconomic imbalances. Slowing global trade, high savings, low r*, EM flows. However, the umbrella in which they all seem to fit under is the world outlined above, a world that saves too much. And what is interesting from both a trading and a macroeconomic point of view, a lot of this was just a policy choice.

Getting out of the pandemic, there are two outcomes for the private sector. One, a liquidity crisis turning into a solvency crisis, or they are saved and develop a massive savings impulse after this ends. This is why all these plans for fiscal involve some sort of debt forgiveness or socializing necessary costs. Policy will be pushed, whether it knows it or not, to "free" private sector balance sheets.

Another example of this, but with very different characteristics has been Taiwan (5th biggest NIIP in the world). In Taiwan, life insurance asset are over 150% GDP. Creating this imbalance has been a central bank that has repressed the exchange rate to defend the tradeable goods sector and now almost more importantly the non bank financial sector which has built up a very large implicit and explicit FX position. These three Asian economies are sending over 1.4 trillion USD into US credit markets.

The savings glut killed monetary policy

This global savings imbalance has created a big problem for monetary policy.

1) It is a position that is effectively short NGDP. If both private and public sector has a savings impulse, both growth and inflation fall. As the world is highly integrated, those conditions are exported. If r* is falling in Asia and Europe, it will be falling in the US as well.

2) So there are two ways excess savings relate to the neutral level of interest. First, it leads to lower growth as money cannot find productive places to invest or spend. Second, a key part of the calculation for the r* is a the demand for safe assets. So growth is slow and savings leads to a heightened demand for safe assets, interest rates around the world fall.

3) This has contributed to a smaller monetary policy impetus. One, it has driven policy rates around the world to the lower bound. But two, it has never really given policy a chance. We know that rate of accommodation (excluding LSAPs/forward guidance) of monetary policy is the stance of policy relative to the neutral level of interest, which of course is unknowable in real time. However, if global savings via slower global growth and an immense demand for safe assets is crushing the neutral level of interest, then monetary policy is not really easing but just keeping pace. If policy can't get inside r*, it's not really easing, it's adjusting. Said another way, savings have forced CBs to cut in order to not be tightening.

r* has become more and more a global phenomena. Data is from Jorda and Taylor, "Riders on a Storm" paper from last years Jackson Hole.

EM has had an uneven relationship with this savings backdrop

The spillover of this global savings backdrop and DM central banks at the lower bound is, the carry trade. In EM, the carry trade was executed in two stages. First, EM's issued in FX denom (Eichengreen original sin), that didn't work. The way EMs fixed this is by issuing a lot more in local currency and given how low DM yields are, INDOgbs or SAGBs, became very attractive. The problem now is original sin redux (Carstens&Shin). It is difficult for these markets to handle this sort of inflow and countries like South Africa, Indonesia, Mexico, end up with around 40% of the local government bonds in the hands of non resident portfolio flows.

So while yes, it is an advantage that low DM rates have forced capital into parts of the world that need it to further their development, it has come at the cost of volatility. These swings in capital flows since the GFC have become the new normal. EM has way bigger issues than capital flows, but these massive oscillations may have ended up doing more harm than good. This is of course nothing new for EM but this backdrop has helped foster a new vulnerability.

Overall: These all seem to be separate macroeconomic imbalances. Slowing global trade, high savings, low r*, EM flows. However, the umbrella in which they all seem to fit under is the world outlined above, a world that saves too much. And what is interesting from both a trading and a macroeconomic point of view, a lot of this was just a policy choice.

Getting out of the pandemic, there are two outcomes for the private sector. One, a liquidity crisis turning into a solvency crisis, or they are saved and develop a massive savings impulse after this ends. This is why all these plans for fiscal involve some sort of debt forgiveness or socializing necessary costs. Policy will be pushed, whether it knows it or not, to "free" private sector balance sheets.